A chronic invasive pest of vegetables, fruits, and ornamentals. Bemisia tabaci vectors several devastating plant viruses and is known to suppress a crop’s normal defenses against pathogens.

Look for oblong white, fly-like insects on the underside of leaves. In the greenhouse, inspect plants for whiteflies weekly, especially hibiscus, poinsettia, roses and bedding plants such as begonia, fuchsia and petunia.

Eggs

Eggs are whitish to light beige in color, but the yolk inside varies from yellow to orange or even purple. The egg is filled with a mixture of water, protein and minerals called albumen. The egg is protected by a thin layer of outer and inner shell membranes and a hard covering called the cuticle.

When the egg hatches, the first immature stage, called a crawler, is barely visible as it moves around the plant looking for a place to settle and feed. It may remain stationary for several days as it passes through the four larval stages, which are wingless, scale-like and resemble a tiny moth. The larvae eat leaves and stems and excrete honeydew, which attracts sooty mold that restricts light from reaching the plant and interferes with photosynthesis.

Each female whitefly can lay 6-20 eggs per day and they are deposited on the underside of the leaf. The eggs begin as a whitish to light beige in colour but the color gradually changes to brown or even purple as the egg matures. Once the egg hatches, it begins to grow and develop a hard shell which takes about 20 hours to form. The shell contains a cavity that carries the nutrients and moisture for growth. During this time, the egg also passes through a section called the isthmus where the shell membrane fibres are produced and a hardening substance called calcite is added to the surface of the shell.

The greenhouse variety of Bemisia tabaci, commonly known as the Q-biotype, causes major problems in vegetable and ornamental crops such as pointsettia, cucumber, tomato, melon, eggplant, squash, watermelon and many other vegetables and flowers. It is also a serious crop disease vector, transmitting plant viruses, including those of the begomovirus group.

These viruses cause significant damage to the plant by blocking its transport systems, leading to wilting and distorted growth. Bemisia tabaci is widely considered one of the world’s worst invasive species and can be found in gardens, fields and greenhouses around the globe. It thrives in warm climates and can develop resistance to a wide range of pesticides.

Nymphs

The larval (immature) stage of whitefly is called a nymph. Nymphs are wingless and are more like moths than true flies (in the insect order Diptera). They feed by sucking plant juices, which cause leaf damage, malformed buds, and distortion of fruits and vegetables. The nymphs are a nuisance on houseplants, and they can also be serious pests of outdoor plants, especially vegetables, fruit trees, and ornamentals. Nymphs can be hard to distinguish from adult moths because they are wingless, but their color may help identify the species. The most common nymphs are the B biotype and the Q biotype, both of which can cause severe damage in greenhouses.

A nymph’s color changes as it matures through the five instars of the nymphal life cycle. Initially, it is pale-green with dark markings on the head and thorax. As it grows, a black spot appears on each prothoracic segment and the wings become noticeably darker and longer. The nymphs also gain spines on their hind tibiae as they change instars.

The last nymph instar is dark green and resembles an adult moth, with the exception of the shorter wing pads. The nymphs are covered with a fine, waxy layer that can give leaves a bearded appearance. The nymphs may leave spirals of white or yellowish wax on the leaves as they spin and move about.

Nymphs are the elf-like personification of the environment in which they live. They are usually reclusive, but they can be friendly to fellow protectors of the wild, such as rangers or druids. Nymphs love frivolity and play as much as fauns, but they can also be powerfully emotional. They can fall madly in love or be crushed by tragedy. The story of Helios’s son Phaethon is one such example.

Historically, nymphs were classified by the place or region in which they lived and by their host plants. For example, the nymphs of ponds or rivers were known as Nereids and the nymphs of lakes or streams were referred to as Nereidiae or Nereidia. Other nymphs were associated with specific deities: some frolicked in the woods with Pan or goatish satyrs, while others accompanied Artemis, the Olympian goddess of wild things.

Adults

Whiteflies are tiny mothlike insects that feed on more than 1,000 different plant species, causing significant damage to crops and ornamentals in fields and greenhouses. These pests can also transmit crop diseases. The most devastating disease vectors among the Aleyrodidae are a complex of two species in the genus Bemisia, including the greenhouse and sweetpotato whitefly (Trialeurodes vaporariorum) and tobacco and tomato yellow leaf curl begomovirus, transmitted by the common garden and greenhouse species, Bemisia tabaci.

A wide range of symptoms indicate a high whitefly population, with the most noticeable being yellowing leaves that may have wilted or choleric spots and often drop prematurely. Heavily infested plants become stunted and slowed in growth, with a general lack of vigor and rapid depletion of nutrients.

Like all Homopteran insects, whiteflies have piercing-sucking mouthparts that attack the phloem of host plants, sucking the sap and weakening them over time. They also secrete a sticky substance, called honeydew, that encourages the growth of sooty mold and restricts light from reaching leaves, further damaging them.

To complete the life cycle, females lay eggs in a moist, protected area such as a crevice or underside of a leaf, where they hatch into larvae within 12 days. Larvae are active feeders that eat the cuticle of their own pupal skin, which then hardens around them as they mature. Once the adult nymphs emerge, they can be found in fields and greenhouses feeding on the foliage of target plants.

All nymphs develop into adults by cutting themselves out of their pupal skin through a distinctively shaped opening, then feeding on the foliage until they are fully grown. They then move to a protected location where they will form a new pupal skin and repeat the process.

As the insects mature, their wings are progressively larger and take on a more elongated shape. They can be distinguished from one another by the way they hold their wings, with greenhouse and sweetpotato whiteflies holding their wings flat, giving them a triangular appearance from above, while bandedwinged and tobacco whitefly (Bemisia argentifolii) hold theirs tentlike over the body at a sharp angle, making them look linear from above.

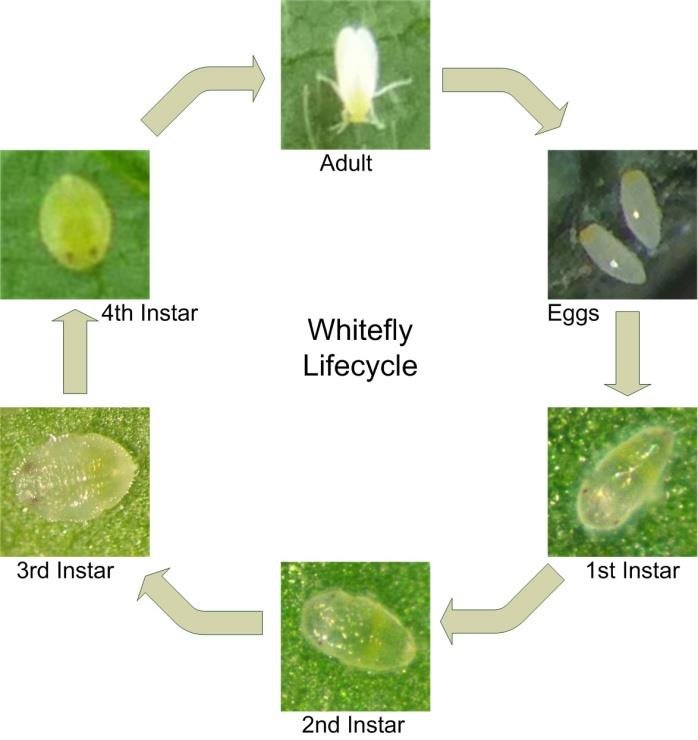

The Life Cycle

Whitefly (Aleyrodidae) sucks plant phloem sap using the proboscis, causing distorted growth and reduced yield in greenhouse plants. It can also transmit viruses of economic importance. Winged females lay eggs on the underside of leaves, which can number in the hundreds. The eggs hatch within five to seven days. The larvae, which are called nymphs, settle on the underside of the leaf and feed by penetrating the phloem with their beak-like proboscis. Nymphs develop through four, successively larger instars. Upon reaching the final, fourth nymph stage, which is often described as a red-eye nymph, feeding stops and the insect molts to become the adult wingless insect.

The timing of the nymphal moults depends on temperature. During the first moult, a nymph will lose its legs and antennae, but will retain its cuticle. The nymph will then settle on the underside of the leaf again and feed. After a few more moults, the nymph will have fully developed legs and a yellowish to dark yellow appearance, and will be flattened in shape as it prepares to become an adult.

Because all stages of the nymphal life cycle require the presence of plants, it is important to keep new stock isolated in a separate bay, bench or area of the greenhouse from existing crops, to avoid accidentally introducing “hitch-hiker” whiteflies from infested material to a clean crop. This may also help to prevent early onset of an infestation in the new crop.

Control

Whiteflies are a significant pest of house plants, greenhouse crops and vegetables in warm climates. They can also damage outdoor gardens and produce a significant yield reduction in commercial vegetable production. The tiny insects can’t survive outside where they don’t have a food source but can persist in greenhouses or in the garden during summer if not managed well. The most important step in controlling whiteflies is prevention. Infestations start from infested plant material brought into a greenhouse or garden, so carefully inspect all new plantings and avoid bringing in material that has a heavy infestation of the pest. In greenhouses, a host-free period can help starve the insects by requiring that all houseplants are kept out of the growing room for two weeks until the insect populations are lowered by spraying and other preventive measures.

Chemical controls are important, both conventional and organic, to keep the population low and manage outbreaks. A combination of a general insecticide, a fungicide and a parasitoid can provide adequate control. However, a single chemical application can increase resistance to that product so it is essential to rotate and use different products and methods of control.

If a garden or greenhouse has an outbreak, the use of yellow sticky traps is effective to monitor adult populations and to find hot spots that need additional treatment. The traps attract and capture the insects as they move over the trap’s surface. However, they won’t eliminate damaging populations and should be used as part of an integrated management program that uses several tactics to manage the pest.

Other control methods include hosing down and vacuuming infested greenhouses and using horticultural oils or neem oil to suffocate the immature insects. Neem oil can burn plants if applied to leaves that are still green so it is best to apply it only to dead or dying plant parts.

If the population is too high to be controlled with these preventive tactics, a least-toxic, short-lived organic fungicide or insect growth regulator can be used to quickly bring it under control. Once the infestation is reduced, the release of predatory or parasitoid insects can help reduce the number of pests and provide long-term control.